Editing and proofing audio files, the last slog to the finish.

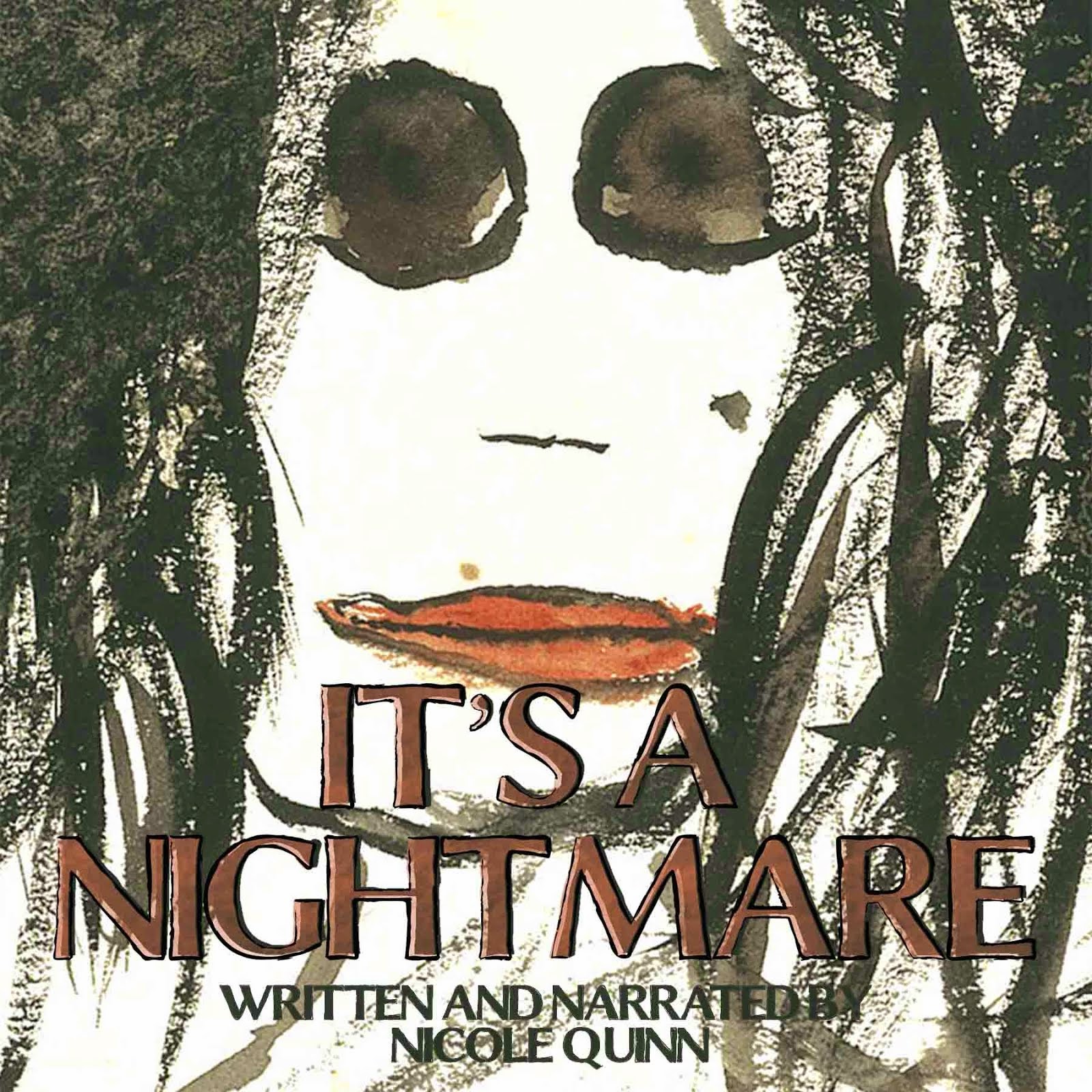

Being the weird girl is never easy, but in a dystopian future where women are licensed as domestic pets, it's a nightmare. Mina is a magical foundling raised by sage off-gridders who teach her to feign compliance. But talent will out, and Mina’s dreams threaten the Night Mare’s rule. Discover the trilogy today!

Wednesday, December 24, 2014

Almost delivered!

Labels:

amazon,

dreams,

dystopia,

fantasy,

fgm,

gendercide,

it's a nightmare,

kindle,

lewy body dementia,

melissa leo,

nicole quinn,

rape,

robin williams,

scifi,

suffrage,

the gold stone girl,

trafficking,

war,

women

Tuesday, December 16, 2014

Lewy Body dementia - It's a Nightmare

My papa has Lewy Body dementia. Hallucinations, Rem sleep disorder, Parkinsons disease symptoms, and vascular blindness. This is what Robin Williams had to look forward to, and he may have already been experiencing some of the indicators.

Maybe he'd already injured someone, a loved one, while acting out dramatic and/or violent dreams while asleep. Maybe his hallucinations were occupying more and more of his waking life. Many with Lewy Body are drug intolerant, experiencing every side effect on the label, and those drugs that normally help with psychotic behavior can push someone with Lewy Body even further into psychosis.

I don't know what the answer is, but I do know that my father put a hospital nurse in the e.r. He's punched, bitten, and hurled himself out of his wheel chair, crept along the floor on all fours to escape a war zone, climbed onto night tables to signal incoming planes, all to escape and/or combat the villains in his dreams, who are in reality caregivers and family members. What I envisioned as shepherding my father to the end of days has become a daily prayer for release.

Knowing what I know now about Lewy Body dementia and its impact on the entire family, I think that Robin Williams may have taken the graceful way out, for more than just himself.

*Lewy body dementia, Parkinsons dementia, and Vascular dementia are cousins. The difference is in the way they present - physical first then dementia, dementia and physical onset simultaneously, etc.

About 20% of all diagnosed dementias are Lewy Body.

Maybe he'd already injured someone, a loved one, while acting out dramatic and/or violent dreams while asleep. Maybe his hallucinations were occupying more and more of his waking life. Many with Lewy Body are drug intolerant, experiencing every side effect on the label, and those drugs that normally help with psychotic behavior can push someone with Lewy Body even further into psychosis.

I don't know what the answer is, but I do know that my father put a hospital nurse in the e.r. He's punched, bitten, and hurled himself out of his wheel chair, crept along the floor on all fours to escape a war zone, climbed onto night tables to signal incoming planes, all to escape and/or combat the villains in his dreams, who are in reality caregivers and family members. What I envisioned as shepherding my father to the end of days has become a daily prayer for release.

Knowing what I know now about Lewy Body dementia and its impact on the entire family, I think that Robin Williams may have taken the graceful way out, for more than just himself.

*Lewy body dementia, Parkinsons dementia, and Vascular dementia are cousins. The difference is in the way they present - physical first then dementia, dementia and physical onset simultaneously, etc.

About 20% of all diagnosed dementias are Lewy Body.

Labels:

amazon,

dreams,

dystopia,

fantasy,

fgm,

gendercide,

it's a nightmare,

kindle,

lewy body dementia,

melissa leo,

nicole quinn,

rape,

robin williams,

scifi,

suffrage,

the gold stone girl,

trafficking,

war,

women

Monday, December 15, 2014

Autopsy: Robin Williams had Lewy body dementia

The hallucination-causing disease may have contributed to his decision to commit suicide

According to his official autopsy, actor and comedian Robin Williams had a disease calledLewy body dementia (LBD), which may have contributed to his decision to kill himself.

People with LBD have dementia and often appear disoriented. According to ABC News, Williams had displayed odd behavior in his final days — notably, he kept several watches in a sock and was “concerned about keeping the watches safe.”

“The dementia usually leads to significant cognitive impairment that interferes with everyday life,” said Angela Taylor, programming director of the Lewy Body Dementia Association in an interview with ABC News. Still, symptoms are hard to spot. “If you didn’t know them you may not realize anything is wrong.”

LBD is fairly common, with 1.3 million people suffering from the illness in the United States, although it largely remains undiagnosed since it shares symptoms with better-known diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

Biologically, the disease stems from abnormal protein deposits in the brain stem where they stop the production of dopamine. In LBD, the deposits spread throughout the brain, including to the cerebral cortex (responsible for problem solving and perception). The main symptom is progressive dementia, although people with the disease may also experience complicated visual hallucinations that could include smells and sounds, trouble sleeping, changes in attention and symptoms generally associated with Parkinson’s disease (which Williams also had).

Typically, patients are diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease first, and then LBD symptoms begin to appear. An examination of Williams’ brain revealed that it had undergone changes associated with Alzheimer’s, in addition to Parkinson’s and LBD.

“Though his death is terribly sad,” Taylor said, “it’s a good opportunity to inform people about this disease and the importance of early diagnosis.”

Labels:

amazon,

dreams,

dystopia,

fantasy,

fgm,

gendercide,

it's a nightmare,

kindle,

lewy body dementia,

melissa leo,

nicole quinn,

rape,

robin williams,

scifi,

suffrage,

the gold stone girl,

trafficking,

war,

women

Thursday, December 4, 2014

Seeds of Suffrage

Labels:

amazon,

dreams,

dystopia,

fantasy,

fgm,

gendercide,

goodreads,

iroquois,

it's a nightmare,

kindle,

melissa leo,

nicole quinn,

nigerian girls,

rape,

scifi,

suffrage,

the gold stone girl,

trafficking,

war,

women

Tuesday, December 2, 2014

Love this Amazon customer review!

Thanks so much for it, Merrick Hansen!

This review is from: It's a Nightmare (The Gold Stone Girl) (Volume 1) (Paperback)

This novel has me hooked. Quinn manages to take science fiction and fantasy, familiar post-apocalyptic themes, and blend them into something indescribably breathtaking. It's like a trip down the rabbit hole. The very first scene had my heart pounding, and I don't think that feeling subsided. I read this all in one day and I feel like I'm still lingering in the world Quinn so masterfully created. Honestly more fantastic than the more popular YA series I have read and seen turned into movies, I hope Quinn's series garners so much more attention and soon. I feel honored to have read this novel and I'll be spreading it like wildfire! This world of dreams and nightmares is absolutely unforgettable.

Labels:

amazon,

dreams,

dystopia,

fantasy,

fgm,

gendercide,

goodreads,

it's a nightmare,

kindle,

melissa leo,

nicole quinn,

nigerian girls,

rape,

scifi,

stone ridge library,

the gold stone girl,

trafficking,

war,

women

Monday, December 1, 2014

Think about it...

Every day women and girls are taught to hate themselves. How many corporations would fail if we didn't believe the advertising?

The power to dream it a new way is yours.

Labels:

dreams,

dystopia,

fantasy,

fgm,

gendercide,

goodreads,

it's a nightmare,

kindle,

melissa leo,

nicole quinn,

nigerian girls,

rape,

scifi,

stone ridge library,

the gold stone girl,

trafficking,

war,

women

Tuesday, November 25, 2014

Ever wonder about the seeds of Suffrage?

http://www.sallyroeschwagner.com/lectures/sisters-in-spirit/

Labels:

caitlin p quinn,

dreams,

dystopia,

eve ensler,

fantasy,

fgm,

gendercide,

it's a nightmare,

kindle,

laurie giardino,

melissa leo,

nicole quinn,

rape,

scifi,

the gold stone girl,

trafficking,

war,

women

Wednesday, November 12, 2014

DISBELIEF

Labels:

.,

a.r.t.,

caitlin p quinn,

dreams,

dystopia,

eve ensler,

fantasy,

fgm,

gendercide,

it's a nightmare,

kindle,

laurie giardino,

melissa leo,

nicole quinn,

rape,

scifi,

the gold stone girl,

trafficking,

war,

women

Tuesday, November 11, 2014

Melissa Leo's Review - It's a Nightmare

What a journey I have gone on!....swallowing in great greedy gulps like one of your demon types all your long hard work!....wow!....fun fascinating and informative!......really well done ...like things that have big play in the world ...and yet deeper and better....and what happens beyond plunging into disbelief?.???......I know you are headed there now!....so very proud to know you!....thank you..and I indeed adore deedee....what a chance to teach the lessons she teaches...I will hope for the day!

Labels:

a.r.t.,

dreams,

dystopia,

eve ensler,

fantasy,

fgm,

gendercide,

goodreads,

it's a nightmare,

kindle,

melissa leo,

nicole quinn,

nigerian girls,

o.p.c.,

rape,

scifi,

the gold stone girl,

trafficking,

war,

women

Wednesday, November 5, 2014

Why They Kill Their Newborns

New York Times

November 2, 1997, Sunday

Section: Magazine Desk

Why They Kill Their Newborns

By Steven Pinker

By Steven Pinker

Killing your baby. what could be more depraved? For a woman to destroy the fruit of her womb would seem like an ultimate violation of the natural order. But every year, hundreds of women commit neonaticide: they kill their newborns or let them die. Most neonaticides remain undiscovered, but every once in a while a janitor follows a trail of blood to a tiny body in a trash bin, or a woman faints and doctors find the remains of a placenta inside her.

Two cases have recently riveted the American public. Last November, Amy Grossberg and Brian Peterson, 18-year-old college sweethearts, delivered their baby in a motel room and, according to prosecutors, killed him and left his body in a Dumpster. They will go on trial for murder next year and, if convicted, could be sentenced to death. In June, another 18-year-old, Melissa Drexler, arrived at her high-school prom, locked herself in a bathroom stall, gave birth to a boy and left him dead in a garbage can. Everyone knows what happened next: she touched herself up and returned to the dance floor. In September, a grand jury indicted her for murder.

How could they do it? Nothing melts the heart like a helpless baby. Even a biologist's cold calculations tell us that nurturing an offspring that carries our genes is the whole point of our existence. Neonaticide, many think, could be only a product of pathology. The psychiatrists uncover childhood trauma. The defense lawyers argue temporary psychosis. The pundits blame a throwaway society, permissive sex education and, of course, rock lyrics.

But it's hard to maintain that neonaticide is an illness when we learn that it has been practiced and accepted in most cultures throughout history. And that neonaticidal women do not commonly show signs of psychopathology. In a classic 1970 study of statistics of child killing, a psychiatrist, Phillip Resnick, found that mothers who kill their older children are frequently psychotic, depressed or suicidal, but mothers who kill their newborns are usually not. (It was this difference that led Resnick to argue that the category infanticide be split into neonaticide, the killing of a baby on the day of its birth, and filicide, the killing of a child older than one day. )

Killing a baby is an immoral act, and we often express our outrage at the immoral by calling it a sickness. But normal human motives are not always moral, and neonaticide does not have to be a product of malfunctioning neural circuitry or a dysfunctional upbringing. We can try to understand what would lead a mother to kill her newborn, remembering that to understand is not necessarily to forgive.

Martin Daly and Margo Wilson, both psychologists, argue that a capacity for neonaticide is built into the biological design of our parental emotions. Mammals are extreme among animals in the amount of time, energy and food they invest in their young, and humans are extreme among mammals. Parental investment is a limited resource, and mammalian mothers must ''decide'' whether to allot it to their newborn or to their current and future offspring. If a newborn is sickly, or if its survival is not promising, they may cut their losses and favor the healthiest in the litter or try again later on.

In most cultures, neonaticide is a form of this triage. Until very recently in human evolutionary history, mothers nursed their children for two to four years before becoming fertile again. Many children died, especially in the perilous first year. Most women saw no more than two or three of their children survive to adulthood, and many did not see any survive. To become a grandmother, a woman had to make hard choices. In most societies documented by anthropologists, including those of hunter-gatherers (our best glimpse into our ancestors' way of life), a woman lets a newborn die when its prospects for survival to adulthood are poor. The forecast might be based on abnormal signs in the infant, or on bad circumstances for successful motherhood at the time -- she might be burdened with older children, beset by war or famine or without a husband or social support. Moreover, she might be young enough to try again.

We are all descendants of women who made the difficult decisions that allowed them to become grandmothers in that unforgiving world, and we inherited that brain circuitry that led to those decisions. Daly and Wilson have shown that the statistics on neonaticide in contemporary North America parallel those in the anthropological literature. The women who sacrifice their offspring tend to be young, poor, unmarried and socially isolated.

Natural selection cannot push the buttons of behavior directly; it affects our behavior by endowing us with emotions that coax us toward adaptive choices. New mothers have always faced a choice between a definite tragedy now and the possibility of an even greater tragedy months or years later, and that choice is not to be taken lightly. Even today, the typical rumination of a depressed new mother -- how will I cope with this burden? -- is a legitimate concern. The emotional response called bonding is also far more complex than the popular view, in which a woman is imprinted with a lifelong attachment to her baby if they interact in a critical period immediately following the baby's birth. A new mother will first coolly assess the infant and her current situation and only in the next few days begin to see it as a unique and wonderful individual. Her love will gradually deepen in ensuing years, in a trajectory that tracks the increasing biological value of a child (the chance that it will live to produce grandchildren) as the child proceeds through the mine field of early development.

Even when a mother in a hunter-gatherer society hardens her heart to sacrifice a newborn, her heart has not turned to stone. Anthropologists who interview these women (or their relatives, since the event is often too painful for the woman to discuss) discover that the women see the death as an unavoidable tragedy, grieve at the time and remember the child with pain all their lives. Even the supposedly callous Melissa Drexler agonized over a name for her dead son and wept at his funeral. (Initial reports that, after giving birth, she requested a Metallica song from the deejay and danced with her boyfriend turned out to be false.)

Many cultural practices are designed to distance people's emotions from a newborn until its survival seems probable. Full personhood is often not automatically granted at birth, as we see in our rituals of christening and the Jewish bris. And yet the recent neonaticides still seem puzzling. These are middle-class girls whose babies would have been kept far from starvation by the girls' parents or by any of thousands of eager adoptive couples. But our emotions, fashioned by the slow hand of natural selection, respond to the signals of the long-vanished tribal environment in which we spent 99 percent of our evolutionary history. Being young and single are two bad omens for successful motherhood, and the girl who conceals her pregnancy and procrastinates over its consequences will soon be disquieted by a third omen. She will give birth in circumstances that are particularly unpromising for a human mother: alone.

In hunter-gatherer societies, births are virtually always assisted because human anatomy makes birth (especially the first one) long, difficult and risky. Older women act as midwives, emotional supports and experienced appraisers who help decide whether the infant should live. Wenda Trevathan, an anthropologist and trained midwife, has studied pelvises of human fossils and concluded that childbirth has been physically tortuous, and therefore probably assisted, for millions of years. Maternal feelings may be adapted to a world in which a promising newborn is heralded with waves of cooing and clucking and congratulating. Those reassuring signals are absent from a secret birth in a motel room or a bathroom stall.

So what is the mental state of a teen-age mother who has kept her pregnancy secret? She is immature enough to have hoped that her pregnancy would go away by itself, her maternal feelings have been set at zero and she suddenly realizes she is in big trouble. Sometimes she continues to procrastinate. In September, 17-year-old Shanta Clark gave birth to a premature boy and kept him hidden in her bedroom closet, as if he were E.T., for 17 days. She fed him before and after she went to school until her mother discovered him. The weak cry of the preemie kept him from being discovered earlier. (In other cases, girls have panicked over the crying and, in stifling the cry, killed the baby.)

Most observers sense the desperation that drives a woman to neonaticide. Prosecutors sometimes don't prosecute; juries rarely convict; those found guilty almost never go to jail. Barbara Kirwin, a forensic psychologist, reports that in nearly 300 cases of women charged with neonaticide in the United States and Britain, no woman spent more than a night in jail. In Europe, the laws of several countries prescribed less-severe penalties for neonaticide than for adult homicides. The fascination with the Grossberg-Peterson case comes from the unusual threat of the death penalty. Even those in favor of capital punishment might shudder at the thought of two reportedly nice kids being strapped to gurneys and put to death.

But our compassion hinges on the child, not just on the mother. Killers of older children, no matter how desperate, evoke little mercy. Susan Smith, the South Carolina woman who sent her two sons, 14 months and 3 years old, to watery deaths, is in jail, unmourned, serving a life sentence. The leniency shown to neonaticidal mothers forces us to think the unthinkable and ask if we, like many societies and like the mothers themselves, are not completely sure whether a neonate is a full person.

It seems obvious that we need a clear boundary to confer personhood on a human being and grant it a right to life. Otherwise, we approach a slippery slope that ends in the disposal of inconvenient people or in grotesque deliberations on the value of individual lives. But the endless abortion debate shows how hard it is to locate the boundary. Anti-abortionists draw the line at conception, but that implies we should shed tears every time an invisible conceptus fails to implant in the uterus -- and, to carry the argument to its logical conclusion, that we should prosecute for murder anyone who uses an IUD. Those in favor of abortion draw the line at viability, but viability is a fuzzy gradient that depends on how great a risk of an impaired child the parents are willing to tolerate. The only thing both sides agree on is that the line must be drawn at some point before birth.

Neonaticide forces us to examine even that boundary. To a biologist, birth is as arbitrary a milestone as any other. Many mammals bear offspring that see and walk as soon as they hit the ground. But the incomplete 9-month-old human fetus must be evicted from the womb before its outsize head gets too big to fit through its mother's pelvis. The usual primate assembly process spills into the first years in the world. And that complicates our definition of personhood.

What makes a living being a person with a right not to be killed? Animal-rights extremists would seem to have the easiest argument to make: that all sentient beings have a right to life. But champions of that argument must conclude that delousing a child is akin to mass murder; the rest of us must look for an argument that draws a smaller circle. Perhaps only the members of our own species, Homo sapiens, have a right to life? But that is simply chauvinism; a person of one race could just as easily say that people of another race have no right to life.

No, the right to life must come, the moral philosophers say, from morally significant traits that we humans happen to possess. One such trait is having a unique sequence of experiences that defines us as individuals and connects us to other people. Other traits include an ability to reflect upon ourselves as a continuous locus of consciousness, to form and savor plans for the future, to dread death and to express the choice not to die. And there's the rub: our immature neonates don't possess these traits any more than mice do.

Several moral philosophers have concluded that neonates are not persons, and thus neonaticide should not be classified as murder. Michael Tooley has gone so far as to say that neonaticide ought to be permitted during an interval after birth. Most philosophers (to say nothing of nonphilosophers) recoil from that last step, but the very fact that there can be a debate about the personhood of neonates, but no debate about the personhood of older children, makes it clearer why we feel more sympathy for an Amy Grossberg than for a Susan Smith.

So how do you provide grounds for outlawing neonaticide? The facts don't make it easy. Some philosophers suggest that people intuitively see neonates as so similar to older babies that you couldn't allow neonaticide without coarsening the way people treat children and other people in general. Again, the facts say otherwise. Studies in both modern and hunter-gatherer societies have found that neonaticidal women don't kill anyone but their newborns, and when they give birth later under better conditions, they can be devoted, loving mothers.

The laws of biology were not kind to Amy Grossberg and Melissa Drexler, and they are not kind to us as we struggle to make moral sense of the teen-agers' actions. One predicament is that our moral system needs a crisp inauguration of personhood, but the assembly process for Homo sapiens is gradual, piecemeal and uncertain. Another problem is that the emotional circuitry of mothers has evolved to cope with this uncertain process, so the baby killers turn out to be not moral monsters but nice, normal (and sometimes religious) young women. These are dilemmas we will probably never resolve, and any policy will leave us with uncomfortable cases. We will most likely muddle through, keeping birth as a conspicuous legal boundary but showing mercy to the anguished girls who feel they had no choice but to run afoul of it.

Two cases have recently riveted the American public. Last November, Amy Grossberg and Brian Peterson, 18-year-old college sweethearts, delivered their baby in a motel room and, according to prosecutors, killed him and left his body in a Dumpster. They will go on trial for murder next year and, if convicted, could be sentenced to death. In June, another 18-year-old, Melissa Drexler, arrived at her high-school prom, locked herself in a bathroom stall, gave birth to a boy and left him dead in a garbage can. Everyone knows what happened next: she touched herself up and returned to the dance floor. In September, a grand jury indicted her for murder.

How could they do it? Nothing melts the heart like a helpless baby. Even a biologist's cold calculations tell us that nurturing an offspring that carries our genes is the whole point of our existence. Neonaticide, many think, could be only a product of pathology. The psychiatrists uncover childhood trauma. The defense lawyers argue temporary psychosis. The pundits blame a throwaway society, permissive sex education and, of course, rock lyrics.

But it's hard to maintain that neonaticide is an illness when we learn that it has been practiced and accepted in most cultures throughout history. And that neonaticidal women do not commonly show signs of psychopathology. In a classic 1970 study of statistics of child killing, a psychiatrist, Phillip Resnick, found that mothers who kill their older children are frequently psychotic, depressed or suicidal, but mothers who kill their newborns are usually not. (It was this difference that led Resnick to argue that the category infanticide be split into neonaticide, the killing of a baby on the day of its birth, and filicide, the killing of a child older than one day. )

Killing a baby is an immoral act, and we often express our outrage at the immoral by calling it a sickness. But normal human motives are not always moral, and neonaticide does not have to be a product of malfunctioning neural circuitry or a dysfunctional upbringing. We can try to understand what would lead a mother to kill her newborn, remembering that to understand is not necessarily to forgive.

Martin Daly and Margo Wilson, both psychologists, argue that a capacity for neonaticide is built into the biological design of our parental emotions. Mammals are extreme among animals in the amount of time, energy and food they invest in their young, and humans are extreme among mammals. Parental investment is a limited resource, and mammalian mothers must ''decide'' whether to allot it to their newborn or to their current and future offspring. If a newborn is sickly, or if its survival is not promising, they may cut their losses and favor the healthiest in the litter or try again later on.

In most cultures, neonaticide is a form of this triage. Until very recently in human evolutionary history, mothers nursed their children for two to four years before becoming fertile again. Many children died, especially in the perilous first year. Most women saw no more than two or three of their children survive to adulthood, and many did not see any survive. To become a grandmother, a woman had to make hard choices. In most societies documented by anthropologists, including those of hunter-gatherers (our best glimpse into our ancestors' way of life), a woman lets a newborn die when its prospects for survival to adulthood are poor. The forecast might be based on abnormal signs in the infant, or on bad circumstances for successful motherhood at the time -- she might be burdened with older children, beset by war or famine or without a husband or social support. Moreover, she might be young enough to try again.

We are all descendants of women who made the difficult decisions that allowed them to become grandmothers in that unforgiving world, and we inherited that brain circuitry that led to those decisions. Daly and Wilson have shown that the statistics on neonaticide in contemporary North America parallel those in the anthropological literature. The women who sacrifice their offspring tend to be young, poor, unmarried and socially isolated.

Natural selection cannot push the buttons of behavior directly; it affects our behavior by endowing us with emotions that coax us toward adaptive choices. New mothers have always faced a choice between a definite tragedy now and the possibility of an even greater tragedy months or years later, and that choice is not to be taken lightly. Even today, the typical rumination of a depressed new mother -- how will I cope with this burden? -- is a legitimate concern. The emotional response called bonding is also far more complex than the popular view, in which a woman is imprinted with a lifelong attachment to her baby if they interact in a critical period immediately following the baby's birth. A new mother will first coolly assess the infant and her current situation and only in the next few days begin to see it as a unique and wonderful individual. Her love will gradually deepen in ensuing years, in a trajectory that tracks the increasing biological value of a child (the chance that it will live to produce grandchildren) as the child proceeds through the mine field of early development.

Even when a mother in a hunter-gatherer society hardens her heart to sacrifice a newborn, her heart has not turned to stone. Anthropologists who interview these women (or their relatives, since the event is often too painful for the woman to discuss) discover that the women see the death as an unavoidable tragedy, grieve at the time and remember the child with pain all their lives. Even the supposedly callous Melissa Drexler agonized over a name for her dead son and wept at his funeral. (Initial reports that, after giving birth, she requested a Metallica song from the deejay and danced with her boyfriend turned out to be false.)

Many cultural practices are designed to distance people's emotions from a newborn until its survival seems probable. Full personhood is often not automatically granted at birth, as we see in our rituals of christening and the Jewish bris. And yet the recent neonaticides still seem puzzling. These are middle-class girls whose babies would have been kept far from starvation by the girls' parents or by any of thousands of eager adoptive couples. But our emotions, fashioned by the slow hand of natural selection, respond to the signals of the long-vanished tribal environment in which we spent 99 percent of our evolutionary history. Being young and single are two bad omens for successful motherhood, and the girl who conceals her pregnancy and procrastinates over its consequences will soon be disquieted by a third omen. She will give birth in circumstances that are particularly unpromising for a human mother: alone.

In hunter-gatherer societies, births are virtually always assisted because human anatomy makes birth (especially the first one) long, difficult and risky. Older women act as midwives, emotional supports and experienced appraisers who help decide whether the infant should live. Wenda Trevathan, an anthropologist and trained midwife, has studied pelvises of human fossils and concluded that childbirth has been physically tortuous, and therefore probably assisted, for millions of years. Maternal feelings may be adapted to a world in which a promising newborn is heralded with waves of cooing and clucking and congratulating. Those reassuring signals are absent from a secret birth in a motel room or a bathroom stall.

So what is the mental state of a teen-age mother who has kept her pregnancy secret? She is immature enough to have hoped that her pregnancy would go away by itself, her maternal feelings have been set at zero and she suddenly realizes she is in big trouble. Sometimes she continues to procrastinate. In September, 17-year-old Shanta Clark gave birth to a premature boy and kept him hidden in her bedroom closet, as if he were E.T., for 17 days. She fed him before and after she went to school until her mother discovered him. The weak cry of the preemie kept him from being discovered earlier. (In other cases, girls have panicked over the crying and, in stifling the cry, killed the baby.)

Most observers sense the desperation that drives a woman to neonaticide. Prosecutors sometimes don't prosecute; juries rarely convict; those found guilty almost never go to jail. Barbara Kirwin, a forensic psychologist, reports that in nearly 300 cases of women charged with neonaticide in the United States and Britain, no woman spent more than a night in jail. In Europe, the laws of several countries prescribed less-severe penalties for neonaticide than for adult homicides. The fascination with the Grossberg-Peterson case comes from the unusual threat of the death penalty. Even those in favor of capital punishment might shudder at the thought of two reportedly nice kids being strapped to gurneys and put to death.

But our compassion hinges on the child, not just on the mother. Killers of older children, no matter how desperate, evoke little mercy. Susan Smith, the South Carolina woman who sent her two sons, 14 months and 3 years old, to watery deaths, is in jail, unmourned, serving a life sentence. The leniency shown to neonaticidal mothers forces us to think the unthinkable and ask if we, like many societies and like the mothers themselves, are not completely sure whether a neonate is a full person.

It seems obvious that we need a clear boundary to confer personhood on a human being and grant it a right to life. Otherwise, we approach a slippery slope that ends in the disposal of inconvenient people or in grotesque deliberations on the value of individual lives. But the endless abortion debate shows how hard it is to locate the boundary. Anti-abortionists draw the line at conception, but that implies we should shed tears every time an invisible conceptus fails to implant in the uterus -- and, to carry the argument to its logical conclusion, that we should prosecute for murder anyone who uses an IUD. Those in favor of abortion draw the line at viability, but viability is a fuzzy gradient that depends on how great a risk of an impaired child the parents are willing to tolerate. The only thing both sides agree on is that the line must be drawn at some point before birth.

Neonaticide forces us to examine even that boundary. To a biologist, birth is as arbitrary a milestone as any other. Many mammals bear offspring that see and walk as soon as they hit the ground. But the incomplete 9-month-old human fetus must be evicted from the womb before its outsize head gets too big to fit through its mother's pelvis. The usual primate assembly process spills into the first years in the world. And that complicates our definition of personhood.

What makes a living being a person with a right not to be killed? Animal-rights extremists would seem to have the easiest argument to make: that all sentient beings have a right to life. But champions of that argument must conclude that delousing a child is akin to mass murder; the rest of us must look for an argument that draws a smaller circle. Perhaps only the members of our own species, Homo sapiens, have a right to life? But that is simply chauvinism; a person of one race could just as easily say that people of another race have no right to life.

No, the right to life must come, the moral philosophers say, from morally significant traits that we humans happen to possess. One such trait is having a unique sequence of experiences that defines us as individuals and connects us to other people. Other traits include an ability to reflect upon ourselves as a continuous locus of consciousness, to form and savor plans for the future, to dread death and to express the choice not to die. And there's the rub: our immature neonates don't possess these traits any more than mice do.

Several moral philosophers have concluded that neonates are not persons, and thus neonaticide should not be classified as murder. Michael Tooley has gone so far as to say that neonaticide ought to be permitted during an interval after birth. Most philosophers (to say nothing of nonphilosophers) recoil from that last step, but the very fact that there can be a debate about the personhood of neonates, but no debate about the personhood of older children, makes it clearer why we feel more sympathy for an Amy Grossberg than for a Susan Smith.

So how do you provide grounds for outlawing neonaticide? The facts don't make it easy. Some philosophers suggest that people intuitively see neonates as so similar to older babies that you couldn't allow neonaticide without coarsening the way people treat children and other people in general. Again, the facts say otherwise. Studies in both modern and hunter-gatherer societies have found that neonaticidal women don't kill anyone but their newborns, and when they give birth later under better conditions, they can be devoted, loving mothers.

The laws of biology were not kind to Amy Grossberg and Melissa Drexler, and they are not kind to us as we struggle to make moral sense of the teen-agers' actions. One predicament is that our moral system needs a crisp inauguration of personhood, but the assembly process for Homo sapiens is gradual, piecemeal and uncertain. Another problem is that the emotional circuitry of mothers has evolved to cope with this uncertain process, so the baby killers turn out to be not moral monsters but nice, normal (and sometimes religious) young women. These are dilemmas we will probably never resolve, and any policy will leave us with uncomfortable cases. We will most likely muddle through, keeping birth as a conspicuous legal boundary but showing mercy to the anguished girls who feel they had no choice but to run afoul of it.

This article was published in the New York Times - I did not write it, and and I am not making a profit off of the article. - Nicole -

Labels:

chronogram,

dreams,

dystopia,

fantasy,

fgm,

gendercide,

goodreads,

inquiring minds,

it's a nightmare,

kindle,

melissa leo,

nicole quinn,

nigerian girls,

rape,

scifi,

the gold stone girl,

trafficking,

war,

women

Thursday, October 30, 2014

The Stone Ridge Library welcomes Nicole Quinn

The Stone Ridge Library welcomes Nicole Quinn who will read from her newest work, It's a Nightmare, on Monday, Nov. 3 at 6:30 p.m. in the Reference Room. It's a Nightmare is the first in the Gold Stone Trilogy set a million years in the future. Quinn will introduce her characters – polar opposites Dream Weaver and Night Mare, as they battle to prevail in their one-continent world of Blinkin. All are welcome. For information, contact the Library Program Office at 687-8726.

Labels:

dreams,

dystopia,

fantasy,

fgm,

gendercide,

goodreads,

it's a nightmare,

kindle,

melissa leo,

nicole quinn,

nigerian girls,

rape,

scifi,

stone ridge library,

the gold stone girl,

trafficking,

war,

women

Monday, October 27, 2014

Merrick of Literature Typeface Review!

http://literaturetypeface.tumblr.com/tagged/fiction

Now let me say that my roommate is a YA fantasy fanatic. This girl cannot pick up a book in Barnes & Noble without it inadvertently being a YA fantasy series. Nicole Quinn’s It’s a Nightmare (The Gold Stone Girl 1)is far better than any of those books I have seen my roommate pick up and I have heard far less about it. How crazy is that? So in my effort to let people know how frakking fantastic this one was, I’m going to start this out by saying: you have to read this book. It is the epitome of a page turner. From the first scene (which literally had my heart pounding), I couldn’t stop reading. I finished the book in a single day and I don’t regret a moment of it.

It’s a Nightmare follows young Mina through a world where women are categorized as “breeders,” inhuman creatures, cattle. Although they are women as we know them, they are the victims of a tyrannical society where rape culture has become a monstrosity I can’t even begin to explain. Women, and the multi-species society in general are taught lessons that I cannot even begin to understand, but sadly enough is not far from modern rape culture (think aliens, tentacle monsters, bird people, and the Night Mare herself, who is actually a demon and just so happens to be the tyrant in charge). Women are considered breeding stock, men are their masters, and ironically enough a demon woman runs the whole show, suppressing individuals ability to dream, think, even look people in the eye. It is actually a nightmare, a completely twisted, dystopian, frightening version of all the worst scenarios you can imagine humanity spinning into.

However, as bleak as this sounds, Mina is hope. She is hope personified, born not of this strange and horrific world. Mina is Born of Tree, found born within a willow tree by Dee-Dee, who raises her as her own and tries to shelter her from the horrifying truths of city life not far outside their doorstep. Dee-Dee and Bubba raise Mina “Off-grid,” outside the city of Winkin where individuals are compartmentalized and categorized and indoctrinated into the Night Mare’s twisted version of society.

Mina is a mystery — she thinks for herself, and has the uncanny ability to teleport through space in times of stress, to “dream” herself elsewhere, to invade other dreams, and she doesn’t know why. She knows she was born of a tree, found wrapped in a mossy cocoon and rescued from her cocoon by Dee-Dee and Bubba, but she doesn’t understand why she is different.

This novel follows Mina through Girl School, where girls are indoctrinated and taught to submit, and when she is evicted from Girl School after a supernaturally charged incident (with butterflies — nothing says magical wood nymph like butterflies), she is taken headlong into a fate-driven journey. She is chosen, later on, to serve the Night Mare herself, to mate with the Night Mare’s only son, and then empowered in the realization that she is the Night Mare’s only equal, her enemy, fated to change the world they live in.

This is fantasy, destiny, and a headlong trip into a world that’s strangely different but not at all different from our own. This is quite honestly a breathtaking novel, an amazing start to a series that’s sure to turn heads and produce films and become a powerhouse of its own.

It is an absolute must read for all YA fantasy enthusiasts. If I could I’d hand out copies of it to all those I see browsing the YA sections of Barnes & Noble. It’s honestly just that good — and this is coming from a guy who really doesn’t ever read YA.

Nicole Quinn, I’m rooting for this novel so, so hard!

Labels:

chronogram,

dreams,

dystopia,

fantasy,

fgm,

gendercide,

goodreads,

inquiring minds,

it's a nightmare,

kindle,

melissa leo,

nicole quinn,

nigerian girls,

rape,

scifi,

the gold stone girl,

trafficking,

war,

women

Thursday, October 16, 2014

Cover of DISBELIEF - book 2 of The Gold Stone Girl Series

Labels:

chronogram,

dreams,

dystopia,

fantasy,

fgm,

gendercide,

goodreads,

inquiring minds,

it's a nightmare,

kindle,

melissa leo,

nicole quinn,

nigerian girls,

rape,

scifi,

the gold stone girl,

trafficking,

war,

women

Tuesday, October 7, 2014

How The World Quickly Stopped Caring About The Kidnapped Nigerian Girls In 3 Simple Charts

http://www.informationng.com/2014/06/how-the-world-quickly-stopped-caring-about-the-kidnapped-nigerian-girls-in-3-simple-charts.html

Posted by: foluso on June 21, 2014

Hayes Brown, an editor at ThinkProgress.org and a blogger conducted a research dedicated to the kidnap of more than 200 girls from the Government Girls Secondary School in the town of Chibok, located in Nigeria’s northeast Borno state by militants from the terrorist group commonly known as Boko Haram on April 14, 2014.

The research is based on 5 Goggle trends charts. Here’s only the part of the article that may be interesting for Nigerian readers:

The girls are still missing. Their mothers still protest in Nigeria’s capital. International assistance is flowing into the country to aid in the search. Despite that, the interest in the plight of the nearly three hundred school-aged girls taken over two months ago has plummeted since the story first became the latest cause célèbre on the Internet. It’s a common enough assumption as to become cliche that interest in news stories, barring large flashy developments, tends to fade over time.

But the data backs up that idea, particularly in the case of the story of the three hundred girls from the Government Girls Secondary School in the town of Chibok, located in Nigeria’s northeast Borno state. According to the data, that interest lasted for roughly a week before sharply dropping to the levels seen today. Since the kidnapping finally made its way into the international press, the story has been shared and tracked on social media through the hashtag “#BringBackOurGirls, serving almost as a brand for the abduction, an easy way to refer to the complex situation unraveling.

Google offers a service called Google Trends which can be used to examine how many people worldwide search for given terms compared to other points over a certain period. Plugging #BringBackOurGirls into Google Trends, modeling the last 90 days of search traffic, shows a surge of interest in the term peaking on Fri. May 9, before a sharp drop-off the following Monday.

The hashtag originated in Nigeria roughly two weeks after the girls’ kidnapping. Searches for the hashtag on Google skyrocketed the third week of the girls’ kidnapping. A drop-off in interest into the hashtag doesn’t necessary mean that interest in the story writ large is also falling. As a way to minimize the chances of that, ThinkProgress also ran a query for the term “Nigeria girls,” a simple shorthand for the story. The results are similar in terms of a clear peak followed by a substantial drop-off in interest.

{read_more}

A small surge can be seen around May 1, the day after families of the kidnapped girls launched their first protest demanding that the government move faster to locate their sisters, nieces, and daughters. Interest began to climb before — as seen with searches for #BringBackOurGirls — reaching an apex on May 8.

By May 12, when a new video featuring Boko Haram leader Abubakar Shekau offering to trade the kidnapped girls for the release of jailed compatriots — and allegedly showing around half of the kidnapped girls clad in full-length jilbābs — emerged, the interest had clearly waned.

The other piece to this story is the involvement of Boko Haram, as the identity of the kidnappers was suspected but unconfirmed for the first weeks of the abduction. Once Shekau released his video listing his demands, the searches for “Boko Haram” on Google worldwide peaked. But much like the other search terms, the interest has since fallen off precipitously, though not to the same degree.

Here’s a search for the terms “Nigeria and kidnapping” for each of the days since the girls were first abducted:

(Click to enlarge)

Despite the lagging interest, events continue apace in the pursuit of the girls and the efforts to rein in Boko Haram. A full international presence has been mobilized in Nigeria. The United States is currently flying both manned and unmanned missions over Nigeria in an attempt to gain intelligence on just where the girls may be located. Countries as far-flung as Israel — who has sent intelligence experts to aid the government — have even contributed to the cause.

Even as the cameras leave the country, Nigerians in the north, where Boko Haram is strongest, are still fleeing the fighting across the border. “In all 250,000 people are now internally displaced, according to the Nigeria Emergency Management Agency (NEMA),” United Nations High Commission for Refugees spokesperson Adrian Edwards said on May 9. “Some 61,000 others have fled to neighbouring Cameroon, Chad and Niger.” But now, Boko Haram’s campaign appears to be following them.

The chance remains that the Jonathan government, which has been sharply criticized for its response to the crisis, could react harshly to such a strong rebuke and what is quickly becoming a referendum on his leadership. So while interest in the tale of Boko Haram and the kidnapped girls is exiting the public imagination around the world, the story remains sharply burned in the minds of Nigerians.

Labels:

chronogram,

dreams,

dystopia,

fantasy,

fgm,

gendercide,

goodreads,

inquiring minds,

it's a nightmare,

kindle,

melissa leo,

nicole quinn,

nigerian girls,

rape,

scifi,

the gold stone girl,

trafficking,

war,

women

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)